DBC Darlings,

I teach at Parsons, and it was with a very heavy heart that I dismissed my students for spring break, wondering if we would return to the classroom when break ended. (Answer: no. We will next convene over Zoom). In an attempt to lift my students’ spirits — and temporarily transport them to another time and place — I recommended accessible, paperback books related to the field of jewelry for each day during their break. I share the list with you below in hopes that the words and stories and histories found in each might lift your mind and your spirits amid the corona crisis.

My last bit of advice: Wear your jewelry, even as you shelter in place. The very act of adornment will provide comfort and add a literal glimmer of hope to your daily lives, as well as your increasingly casual, work-from-home wardrobes.

Stay well, x

I recommend this book, specifically, because of its chapter on diamonds (Chapter Three, “Carbon Copy”). Pyne writes about the history of lab-grown diamonds, comparing natural to “non-natural,” and questioning what makes one more real than the other. The beginning of the chapter is dense but worth plowing through.

This novel chronicles the notable provenance of a starfish brooch designed by Juliette Moutard for the French firm Rene Boivin, in the early twentieth century. The story sheds light on the contemporary jewelry business and the way in which provenance affects pricing. Both Moutard, and Suzanne Belperron (one of my favorite jewelry designers), worked for the house of Boivin and, finally, are getting the recognition they deserve. The downside: their original works of art are now very expensive at auction.

I mention Cellini when I lecture on the Renaissance, as he was a well-known goldsmith who worked in Italy and France and embodied the idea of the jeweler as an artist. There was no distinction among the arts (fine, decorative, sculptural) during the Renaissance because all artists trained and worked together. Cellini’s stunning, sculptural Salt Cellar, which is known as the “Mona Lisa of the decorative arts,” is an example of the cross-disciplinary approach to art at the time. In his autobiography, Cellini writes about the Salt Cellar, the difficulty in cutting diamonds, and what it was like to work for different monarchs and popes. This is a great primary source on sixteenth-century life and art.

Stewart’s book profoundly changed the way I see and study objects. Why do we think the monumental is more important than the miniature? Stewart examines the cultural (and sometimes curatorial) constructs that contribute to the bias in how we see things, look at things. The book is incredibly dense and packed with theory but manageable if you take it one chapter at a time.

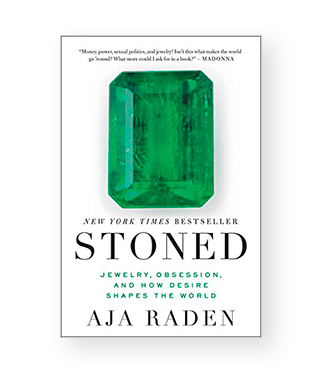

Raden’s book is much less dense and academic than Stewart’s but equally as germane to the study of jewelry. It’s pop culture, history, and anecdote woven into a very readable and enjoyable tale about how objects shaped (and continue to shape) our world—from the diamond necklace that Louis XV commissioned for Madame du Barry to solitaire engagement rings.